Table of Contents

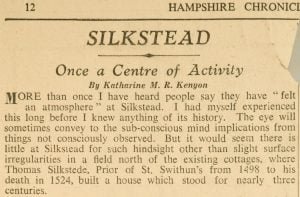

Silkstead – Once a Centre of Activity

From the Hampshire Chronicle, 31 December 1960

Hampshire Records Office Item TOP78/3/8 and 12M73/Z6, reproduced with permission from the family of Miss Kenyon and by courtesy of the Hampshire Chronicle

Katharine M R Kenyon

MORE than once I have heard people say they have “felt an atmosphere” at Silkstead. I had myself experienced this long before I knew anything of its history. The eye will sometimes convey to the sub-conscious mind implications from things not consciously observed. But it would seem there is little at Silkstead for such hindsight other than slight surface irregularities in a field north of the existing cottages, where Thomas Silkstede, Prior of St. Swithun’s from 1498 to his death in 1524, built a house which stood for nearly three centuries.

There is no trace of the thirteenth-century hall, nor of the gated walls (built one supposes of flint) which for centuries enclosed it, and the various farm buildings and dwellings of the bailiff and farm labourers.

But Silkstead was not only bustling with life when it was farmed by the Benedictines of Winchester Priory. Its activity and cultivation go back into the Dark Ages and onward into the 18th century. It must have been cleared from forest in very early times, if not while the Roman landowners in their large heated villas were still here in Hampshire, then very soon afterwards, by Saxon settlers. Close by at Undy’s Hill, Roman coins and pottery have been found, and a little bronze female head, stated by the British Museum to be provincial Roman work with Celtic influence in its treatment.

After the dissolution of the monasteries Silkstead was still farmed with ups and downs as before, but usually profitably, through generation after generation, while at the turn of the 17th century until 1745 it housed a Roman Catholic school. We may remember, too, that in the summer of 1603, when the new King, James V., required accommodation for his Judges owing to plague in London, it was found for them in Winchester, and the College was sent out to Silkstead, as it was also for eight months in 1625-26 while plague raged in Winchester. This quiet spot has been noisy with young life.

Yet even to the most romantic it appears strange that in so quiet a place, after so long a period of isolation, that a sense of vague mystery, of something that had been “different from now” should unexpectedly make itself felt to sonic of those who come upon it in their walks. lt is not difficult to imagine reasons for a building to hold an “atmosphere” and to stimulate curiosity by the unanalysable, but it does seem strange that a small space of land which has undergone centuries of change by cultivation and by natural growth and decay, should do so. Here and there it seems to happen, and Silkstead appears to be one of such places.

The late Mr. J. S. Drew, in his book on Compton, gave much information about Silkstead: in the Cathedral library in the card index made when he was examining the manor rolls (written, it must be remembered, in mediaeval Latin). Here I am attempting to set down in faint picture form some of the facts to be found there.

Behind high gated walls stood most of the farm buildings, and a hall built in 1267 with rooms for the Prior of St. Swithun’s when he came over from Winchester with his “esquires” and servants. It had been erected on the site of an earlier building, and to it was later added a chapel. In 1311 a herb garden was made “next” to the chapel, but it is not clear whether this was within or outside the walls. Outside the East Gate was a large garden, for it contained ash trees (later used to make benches and tables) and even had turved walks. It was not however always kept in perfect order for there are entries in the rolls recording payments for clearing brambles.

A big sheep-shed with thatched roof and wattle and daub walls was also outside the East Gate, and a pond. Another sheep-shed was some distance away at Northbury. The East Gate had a room over it and this was thatched. West and North and Great Gates when needing repair are also mentioned, and I think it possible that the North and Great Gates are the same. There is no mention of a southern gate, but it would seem obvious that the most convenient and therefore principal entrance would be from the north along what is now known as Silkstead Lane.

The Great Gate also had a room over it, and the roof of this was tiled; but even its name shows that it was of more importance than the East Gate; in 1388 a small gate was made beside it which apparently had a grille in the door. In 1318 an unnamed gate, perhaps the Great Gate, had become ruinous and was rebuilt; some of the old timber was used, but two sawyers were working on five oak trees for nearly a month for this gate, and four carpenters for seven weeks; four thousand tiles were needed for the roof. In 1361 two men were thatching the East Gate for 84 days. These two entries may help to give a rough idea of the size of these gates.

Within the enclosing walls were many buildings, erected, no doubt, against the walls. Some were thatched and some were tiled, and an entry of the cost of tiling the wall between the kitchen and one of the gates must, I think, refer to the roofing of whatever building stood there. The kitchen was, as was usual, a separate building and was thatched. In 1461 a new one was built, of which more presently.

There was a granary, a dairy, houses for cattle and pigs, a “press-house” for making cider and wine, a Great Barn and at least one smaller one, a hay-shed, stables for about twelve horses, and a pigeon-house. This latter was built in 1307 and was stocked with 238 birds from Michelmersh and Houghton. It was built of flints by a mason named Adam, another mason raised the walls higher, and three carpenters were at work on it for about three weeks; the roof was covered with lead. I am not sure if all these buildings were within the walls. Somewhere without them was an orchard (cider-making was evidently important), and for a time a vineyard.

Until the Black Death in 1349, eleven labourers (some with families) lived here. Then there is no record for six years. Mr. Drew wrote that the 1348 roll “was made up as usual in the November or December, the script is as beautiful as ever,” but not till the autumn of 1354 is there another. There were then seven labourers instead of eleven, and only 154 acres under the plough instead of 247, and at least ten fewer plough-oxen. It is common knowledge that after the Black Death those who had previously been bound to render service to the manor on which they lived, began to compound for wages instead. The Priory rent roll for Compton was halved, many names never re-appear, whole families were wiped out.

Thirty years later William of Wykeham was asking the King to remit the tithes at Weeke because this parish had never recovered from the Black Death. At Silkstead, things seem to have got back to normal within a short time. It is interesting to note that wages were no higher, and sometimes lower, than before the pestilence. It would seem that for a time all were impoverished. Wealth, as well as food, then came from cultivation. It is possible that, apart from sickness, some died of starvation.

To go back a little in this attempted sketch of Silkstead. In 1314, after “a great wind,” stables, cart-house, cattle-shed and kitchen were all damaged by the fall of one tree and had to be re-thatched. The roof of the hall also suffered in this gale, but as it was tiled it only had to be mended in places. Expenses for 1315 show that the granary, the Great Barn, and the “sergeant’s” chamber were also tiled. The sergeant would be what we now name bailiff. He supervised the work of the other men, some apparently feathering their nest at the same time.

It is interesting to notice how widespread were local contacts. We have noted that pigeons for the new cote were brought from Michelmersh and Houghton. Osiers for the sheep-hurdles also came from Michelmersh, though “our own” were used too, whether near Silkstead or from Winchester is not apparent. From Morestead came the timber for building the Great Barn. That for the hall came from Crondall, and stone from Brixedon, which the V.C.H. gives as either Bursledon or Brighstone in the Isle of Wight. Boards for the hall were bought in Southampton and iron for metal work at St. Barnabas’ Fair in London. It was roofed with 92,000 tiles. Was there a tile kiln handy? So many buildings here were tiled from earliest times that it would seem there must have been. At some seasons sheep were sent to graze in the rich valleys of Weeke. Peacocks were sent to the Abbess of Romsey.

From 1318 to the time of the Black Death there are several entries of horses belonging to the King or to great nobles being at Silkstead for short periods. With the payment received there is also invariably money paid out to prevent pillaging and damage. And as we notice these entries we get sudden glimpses into a dark and turbulent past, hitherto perhaps only known to us as half-forgotten statements in long-ago school books.

In 1325, for instance, the “war horses” of Edward II. and of the elderly Hugh le Despencer, Earl of Winchester, were here. Mr. John Hervey, in his book, “The Plantagenets,” prints a letter from Edward II., dated December 1st, 1325, to his Queen, Isabella (the She-Wolf of France) asking her to return from France, and taking her to task for her enmity to Hugh le Despencer. Next year Isabella had, indeed, returned, with an army, and soon the Earl’s head was displayed over one of Winchester’s gates, and in 1327 the King was murdered in Berkeley Castle.

In 1330 the horses of Edmund Woodstock, Earl of Kent, were at Silkstead. He was the youngest son of Edward I., had joined the false and cruel Queen Isabella and her lover, Mortimer, in their campaign against Edward II., had been appointed one of the Council to govern for the fifteen-year-old Edward III. but in 1330 was beheaded outside Winchester Castle by a criminal fetched from the dungeon to do a deed refused by others. So runs the story, and also that his body was buried secretly by night in the chapel of the Castle.

The skeins of silk at the bottom of the image form part of his “rebus”. The rebus was a commonly-used device in mediaeval times, especially among ecclesiastics, a punning pictorial representation of a name. The second part of Thomas Silkstede’s rebus would have been a horse, or “steed”.

One cannot help wondering where the “war horses” were stabled at Silkstead. Even if the farm horses were turned out into a hedged enclosure, which appears in the rolls from time to time as having manure collected from it, the stabling was not very extensive. Saddles and trappings would need dry cover too. In 1345 the place must have been uncomfortably crowded with “servants” and horses of the King and Queen and the Earl of Derby on their way to France.

The men, of course, would doss down on straw on the floor of the hall; this was common practice for long after. The last entry of this sort is in 1348, the year before the Black Death and two years after Crecy. On this occasion horses belonging to the King and to the Black Prince were there, and money was paid out to their men to prevent their requisitioning farm-carts.

After 1396 the farm was no longer managed by a “sergeant” for the Priory, but was let. In 1445 a certain John Harries became the tenant, he who replaced the ancient kitchen; I include this fact in the sketch of Silkstead because Mr. Drew gives what seem to be completely conclusive reasons for supposing that this man was the father of Thomas Silkstede, “the great Prior of St. Swithin’s who built the easternmost bay of the Lady Chapel and gave to the Cathedral Church some of its most beautiful woodwork,” and any detail about his parents must be interesting.

The kitchen was built in 1461 when their son (if he were the future Prior) was about ten years old. John Harries carted the timber (it is not stated from whence) and two sawyers cut it up. For fifty-four days two carpenters were at work on the framework. Harries or his own labourers filled in the wattle and daub. Three thousand tiles were used for the roof.

John Harries died in 1465 and his widow, Edith, took the farm on. Mr. Drew states that she kept the accounts “in apple-pie order.” Two years after her husband’s death there is an entry in the roll for the wages of two men working on the roof of the Prior’s chamber with the added comment, “where it was greatly needed.” This little sentence makes it easy to imagine not merely a business-like woman, but a shrewd mother looking to her son’s future, or possibly one grateful for notice already taken of him by Prior Westgate, and consequently seeing to the comfort of the great man when he rode out from Winchester for a brief interlude at Silkstead.

The manor house built by his successor, Prior Silkstede (whose name is played on in the carving of the cathedral pulpit and elsewhere) was mentioned at the beginning of this article. It would be nice to think that as a little boy he watched at every opportunity with fascinated and curious eyes the work at his home on the new kitchen, humble though it was in comparison with what he would create in the great cathedral.

About the Author

Katharine Mary Rose Kenyon (17 July 1887 – 18 March 1981)

Katharine (“Kitty” to her family) Kenyon lived in Hampshire for many years. She had a keen interest in local history and the local countryside.

She was Secretary of Winchester CPRE from 1937 to 1956 and afterwards a Vice-president of the Hampshire branch. The Winchester branch of CPRE Hampshire had been formed as recently as November 1935, with Compton architect Herbert Kitchin serving as Secretary for its first meeting.

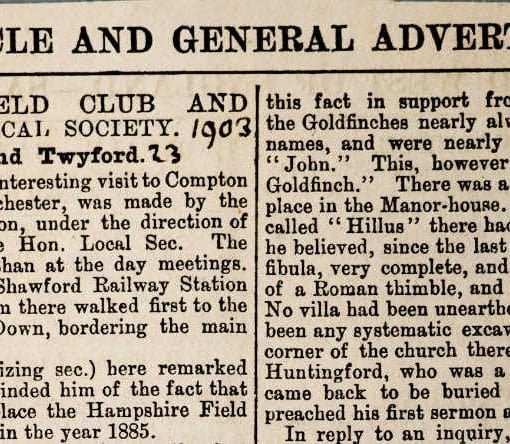

She was a member of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society. The Field Club’s 1943 membership list shows her address as Yew Tree Cottage, Colden Common. By 1955, she was living at The Drove, Twyford, where she remained until her death in 1981.

She was a prolific writer of articles and short essays which appeared in the Hampshire Chronicle, The Times, and Country Life.

She never married, and much of her collection of published articles and newspaper cuttings on archaeology and local history is now in the Hampshire Records Office archive.

Publications

Some of her published articles were reprinted as collections or individual booklets:

- Here and There, but Mainly in Hampshire. Paperback, published by Gilberts Bookshop, Winchester, 1966

- The Living Fields. Paperback, published by Warren & Son Ltd, Winchester, 1968

- Keats in Winchester. A 20-page booklet published by Keats-Shelley Memorial Association, London (1965). An updated version of a 1946 article.

- Benjamin Franklin at Twyford. A 15-page booklet published by Warren & Son Ltd and H.M. Gilbert, 1947. Reprint of a 1946 article.

- A House that was Loved. A book about her childhood home of Pradoe, published by Methuen in 1941. This now rare book fetches high prices from speciality book-sellers.

Family background and early life

Katharine Kenyon came from an old Shropshire family of lawyers and military people.

Her great-grandfather, the Hon Thomas Kenyon, was the third son of Lloyd Kenyon, 1st Baron Kenyon of Gredington, KC, MP, PC, some time Attorney-General and Master of the Rolls. In 1803, the same year that he got married, Thomas bought the country house, park and estate of Pradoe, 12 miles from Oswestry. Pradoe was to become the family home for more than two centuries.

Thomas was Clerk of the Outlawries Court, King’s Bench. He spent much time over the next few decades extending the house and landscaping the park and gardens.

His eldest son, John Robert Kenyon, QC, was chairman of the Shropshire Quarter Sessions and held the office of Recorder of Oswestry. He was also the Vinerian Professor of Common Law at Oxford University. Before the 1755 bequest from Charles Viner establishing the Vinerian Chair, students at Oxford and Cambridge could only study Canon Law and Roman (Civil) Law. To learn about the more practical Common Law, you had to study at the Inns of Court.

Katharine’s father, Maj-Gen Edward Ranulph Kenyon C.B., C.M.G, was the second son of John Robert Kenyon. We assume that he inherited the family home of Pradoe because his elder brother died without issue. In the First World War, he was mentioned in despatches five times and was wounded. He was Chief Engineer of the 3rd Army between 1916 and 1917 and Deputy Controller of Chemical Warfare in 1918.

E.R.Kenyon’s eldest child, the only son to survive infancy, was Lt. Col Herbert Edward Kenyon D.S.O. He also fought in the First World War and was mentioned in despatches four times. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre Belgian and the Distinguished Service Order (D.S.O.)

Katharine Mary Rose Kenyon was E R Kenyon’s oldest daughter. She served as a VAD in France in the First World War, in the No 4 General Hospital in Camiers, just south of Boulogne.

Her short piece “The First Armistice Day”, dated November 1960, appears in The Living Fields. 42 years on, she recalls her feelings as a young VAD on that day.

In the series of First World War books by Lyn Macdonald, Kitty and her younger sister Winifred (Win) are quoted several times in Roses of No-Man’s Land, which tells the story of the nurses/VADs on the Western Front. This 1980 book was the inspiration behind the 2014 BBC TV series “The Crimson Field“.