Hampshire Chronicle and General Advertiser 23 May 1903

Hampshire Field Club and Archæological Society – Compton and Twyford

A somewhat short, but interesting visit to Compton and Twyford, near Winchester, was made by the club on Tuesday afternoon, under the direction of the Hon. Secs. and the Hon. Local Sec. The attendance was smaller than at the day meetings. The party assembled at Shawford Railway Station at half-past two, and from there walked first to the chalk pit on Shawford Down, bordering the main Southampton Road.

Mr. Shore (hon. organizing sec.) here remarked that a gentleman had reminded him of the fact that Shawford was the first place the Hampshire Field Club visited as a society, in the year 1885.

Mr. Lashmore: And the chalk pit was the first thing we officially looked at.

Mr. Shore went on to remark that the fossils to be found in the pit were those of the upper chalk, and in the Hartley Museum, at Southampton, there was a representative series which had been obtained from the pit at different times.

Mr. Dale (hon. general sec.) mentioned that on the occasion of their former visit to Shawford that distinguished geologist, Mr. W. Whitaker, was with them, and he pointed out that they were at that spot very near the top of the chalk, and that somewhere between there and Winchester there was a great fault, which had thrust the chalk down, so that St. Catherine’s Hill was a little lower geologically in the strata.

Mr. Dale mentioned that the chalk pit on the west side of the road was the better in which to find fossils, and several of the company went with him, and in a minute or two Mr. Dale brought to light a specimen of the Holaster pilula. He pointed out the distinctive shepherd’s crown, and said the specimen was fairly common there. In the gravel beds at Eastleigh he had found several little flint Holasters like this, which went to show that the gravel at Eastleigh was from the waste of the chalk up on these hills. Mr. Dale also found one of the circular fossils coscinoporæ, a sponge-like organism. He mentioned it was believed that Palæolithic man used these fossils as beads, and on one occasion he (Mr. Dale) met a gravel-digger at Eastleigh who told him he found lots of the fossils, and on asking him what he did with them the reply was that he kept them until he had got 100, and then put them on a string; the man had three or four such strings and he bought these of him. Here, then, was an instance of an untaught gravel-digger doing unconsciously what Palæolithic man was credited with doing.

The party next walked to Compton Church, where they were met by the Rector (the Rev. A. H. Blake). Outside the church at the south-west corner Mr. Shore remarked that the Club had recently visited Bembridge limestone quarry at Quarr, in the Isle of Wight, they found that stone was used in many Hampshire churches, there was a great deal of it in Winchester Cathedral, and they had seen it as far north as Burghclere, but the latter was not surprising, seeing that it was near the Bishop’s ancient seat at Highclere. In some of the stone of Compton Church there were the characteristic Bembridge features. It was an excellent plan if people got into a mess to get out of it, and since they met at Winchester the Hampshire Field Club had, he believed, got into a little mess. They said something on Worthy Down about a grey-wether stone; he certainly did not say himself that the stone was in situ, though some member of the Club might have done so, but for that he was not answerable, although the stone might well have been in situ, seeing that plenty were on the chalk hills. The main offence, however, was that the stone was not in situ. He certainly did say he had heard it associated with a case of suicide, but it appeared that it was a man died suddenly on the spot 25 years ago, and the stone was moved there as a memorial. That grey wether was far more ancient than anything Norman, Saxon, or Roman, and, therefore, it was not an instance of their examining something that was not ancient, but they were looking at a stone ancient beyond human calculation. And here was another such stone – the foundation stone of Compton church – put there in all human probability a thousand years ago. Grey wethers exist over parts of Hampshire; they were called grey-wethers because of their extreme age, and when seen on Downs they looked not unlike a flock of sheep. Some of their friends might have had a laugh – he did not say Winchester or Southampton people had had a loud laugh, because they were too well bred in deportment not to know this, that it is the loud laugh that shows the vacant mind.

Entering the church Mr. Shore called attention to the very beautiful doorway, which he remarked was one of the best examples of a Norman doorway to be found in the smaller village churches of the country. The font, he said, was probably not so old as the church – he should not put it as of Norman time. Thirty generations may have been baptised in the font, and no new font, however elaborate, would ever, in his opinion, repay the church for the loss of that very ancient font. He pointed out the interesting fact that the font, like others in many parts of Hampshire, afforded an illustration of the order in Synod of the thirteenth century, that fonts should be locked and their covers secured in order that baptismal water should not be taken away for purposes of incantation. Mr. Shore also remarked that they were assembled in a church as to which the parishioners had lately had to express an opinion as to whether the church should be enlarged or re-built ; he was glad to find that all parties were agreed on the one point with which they as an Archæological Society should like to associate themselves, viz., the complete preservation of the old building.

Mr. N. C. H. Nisbett referred to some of the architectural features. The church was interesting, as no, doubt, it was one of those spoken of as belonging to the great manor of Chilcomb. The original plan of the church was much like that at Chilcomb; there was a very narrow chancel arch at Chilcomb, and, no doubt, the original Norman chancel arch of Compton Church was a narrow one. When the alteration was made, about the 13th century, it would seem as if they determined to make the new arch as wide as possible. It was also interesting to note that the beautiful Norman doorway was not on the side on which they usually found the principal door, and the reason was that the principal approach to the church, as now, passed on the north side – it was evidently part of the loop road running between the two Roman roads, one from Winchester to Southampton, and the other to Fareham. Three of the small windows, and possibly one above, were Norman; on the west was a Perpendicular window, rather late work, and almost identical with one at Chilcomb. In the chancel there were 13th century windows. In the east window on the north side there is a fresco, apparently 13th century work. The Rector suggested the figure might be that of St. Swithun, but Mr. Nisbett said there was no distinguishing symbol, and the figure, though that of a bishop, was holding a book in his hand, which was not connected with St. Swithun. Someone else suggested it might be that of St. Thomas à Becket, but Mr. Nisbett said the figure would not agree with that.

Mr. J. B. Colson made a few supplementary remarks, in the course of which he expressed himself as not quite in agreement with all Mr. Nisbett had said as to the chancel. He also mentioned that a gallery at the western end was removed about 30 years ago, and that at the time the church had high pews.

Mr. Shore said before they examined the fresco in the chancel he might mention a few facts which led to the conclusion – of which there could not be much doubt – that the figure was intended for St. Swithun. Compton Church was interesting to them, not from its actual antiquity, but from the early associations of the parish. Those early associations went to the very establishment of Christianity in ancient Wessex. The land formed part of the great manor of Chilcomb, and they might find information relating to Compton in the Cathedral Records relating to St. Swithun’s Priory, and in the Diocesan Registers of Bishop de Asserio and Bishop Sandall, edited by Mr. Baigent, and in that of Bishop Wykeham’s Register edited by Mr. Kirby. When they came to think that Cynegils, the great Christian King of Wessex, gave the land all round Winchester to the church of St. Peter, and that his son was the first to begin to build in Saxon times, then it was certain that Compton must be included, and when we read in Domesday Book about the manor of Chilcomb it was practically more or less the same manor. They found nine churches mentioned, and they could identify six quite close to Winchester – St. Faith, now gone, Sparsholt, Wyke, Winnall, Compton, and Chilcomb. The two oldest names – they were Saxon – were associated with Compton and Chilcomb; Sparsholt was a wood coming from an enclosure; Wyke must have been the outlying part of something; Winnall he would not express any opinion about – and St. Faith was a dedication name. It was interesting to know that Chilcomb was a chapel whilst Compton was a church; if Chilcomb was a chapel without the prerogatives of a parish church, and if Compton was a church there must have been greater importance attaching to that little building in ancient time. The proof that Chilcomb was a chapel and Compton a church they would take from the Papal record, the entry being as follows: –

“Confirmation by the Pope to the Monks of Winchester of the following, inter alia : – ‘The chapel of Chiltecumbe, and the churches of Compton and Whitchurch for the anniversary of Bishop H, the land at Cnoel for the anniversary of King Henry, the land at Childenoel for that of Bishop Godfrey, the church at Elendon for making books, and the church at Littleton for receiving guests. 5 Ides Mar. 1235.’ ” (Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers I. 21).

“Bishop H” meant Henry de Blois, the founder of St. Cross. There were two other records relating to Compton in the Papal Registers, which were as follow : –

“Indult to William de Braham to retain a moiety of the rectory of Wirtham in the diocese of Norwich and the church of Compton in that of Winchester given him by the Bishop-elect of that See, their value together hardly exceeding £20. 3 Ides July, 1259. 5th Alexander IV.” (Calendar of Entries in the Papal Registers I. 365).

“To Raimond Pelegrini, Canon of London, Mandate at the request of the Bishop of Winchester to make provision to William de Meon, rector of Compton, value 20 marks, of a canonry of St. Mary’s, Winchester, with expectation of a prebend. 13 Kal July, 1343. 2 Clement VI.” (Cal. Extr. Papal Registers III. 99).

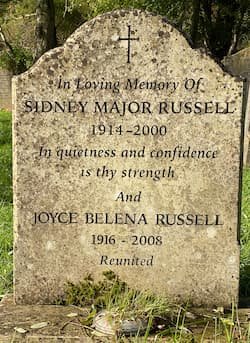

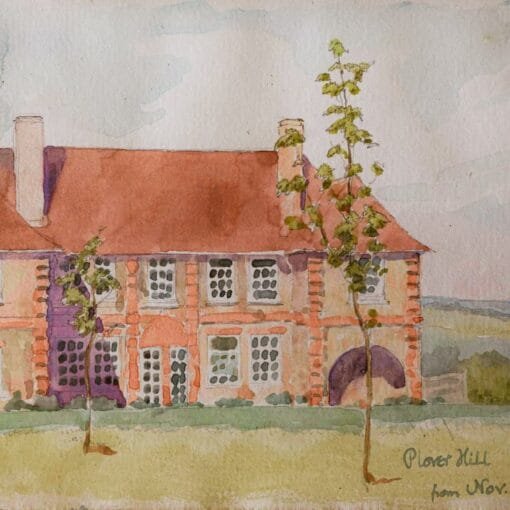

The Rector said there were one or two points of local tradition. Just across the main road on the left-hand side was the old Manor house, or home of the Goldfinch family, for hundreds of years people of importance in the parish, next to the Harrises, of Silkstead; the latter, he supposed, were the most important people in that district, and there were constant records of the Harrises being buried in linen instead of woollen. The tombstones of the Goldfinch family were on the north side of the church, and one was of interest as being that of Richard Barnard Goldfinch, and the story was that at the time the Parliamentarians besieged Winchester the general in command of the forces was Gen. Bond, and when it became known that the heir of the house of Goldfinch was going to be baptised the soldiers agreed to keep one of the barrels of ale unbroached in order that it might be used at the christening of this young Goldfinch, provided he was called after the name of the general. There was this fact in support from the tombstones, that the Goldfinches nearly always used single Christian names, and were nearly all plain “Richard“ or “John.” This, however, was “Richard Barnard Goldfinch.” There was a most interesting old fireplace in the Manor-house. On the site of the house called “Hillus” there had been many Roman finds, he believed, since the last visit of the Field Club – a fibula, very complete, and also a very fine specimen of a Roman thimble, and several pieces of pottery. No villa had been unearthed, because there had not been any systematic excavation. At the south-east corner of the church there was the tomb of Bishop Huntingford, who was a curate of Compton, and came back to be buried near the place where he preached his first sermon and began his ministry.

In reply to an inquiry, Mr. Shore said the old Roman road could be traced running along side the more modern main road between Compton and Otterbourne, though it was over-grown in parts.

The party walked towards Twyford by way of the road passing the old manor house at Compton, and had intended crossing the meadows, but the pathway through the withy beds leading out to the old barge river was ankle deep in water, and only four or five of the party ventured, the rest making a detour and rejoining the others at the footbridge where the meadow path from Shawford to Twyford ends. Here close to the river bank are two large grey wether stones.

Mr. Shore said these were sarsen stones of the same kind as the ones they saw on Worthy Down. It was impossible to say – perhaps almost in any case – whether these stones had been moved; certainly they had moved downwards if not longitudinally; they had moved from a higher vertical position downwards, because the strata in which they were formed had all disappeared, some becoming hardened, and others passing gradually away to sand in the course of centuries. Some of their Southampton and Winchester friends had been having a laugh at the club, but if they wished to realise the age of such stones as this they must study astronomy and learn something of the great cycles of movement in the celestial body which showed no incalculable periods of time. If we looked down into this terrestrial globe we found evidences of vast ages in the removal of great masses which lay on the chalk. This all showed us not only to look to an eternity in the future, but that there was one behind us. If their friends who were inclined to make a laugh at the Hampshire Field Club chose to read Shakespeare they might find something applicable to themselves in the words of Hamlet: –

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

So he thought they might leave the sarsen stones – they were quite able to take care of their antiquity.

A few minutes’ walk brought the party to Twyford Churchyard, where Mr. Shore said the main reason they had come there was to see the wonderful old yew tree – the church was not ancient, and there was nothing much to look at in the interior of the building. There was nothing like this tree in the county, he meant as to shape – there were older trees, at Selborne there was an older tree, but there was nothing in the county that spread out in the way this tree did. Mr. Shore again mentioned his theory that the planting of yews in churchyards was because of the symbolism, the power of the tree to renew its youth. In old trees they saw the new wood mingling with the old – such as those at Selborne and Hayling Island, and he thought at Tisted – but this Twyford tree seemed too young. Mr. Dale said he should not estimate the age of the tree at much over 600 years. Mr. Shore: All that. They must have begun to take great care of the tree 300 or 400 years ago. In answer to an inquiry Mr. Shore added that the clipping of yew trees came in largely with the Restoration, and mainly as the result of Charles II. having lived in Holland.

Mr. Andrew Twitchen remarked that the people of Twyford believed the tree to be 1100 years old.

Mr. Shore said there might be some tradition handed down. He should be sorry to deprive Twyford people of their antiquity, let them cling to it till it was upset.

The programme as arranged ended here, but several of the members devoted further time to natural history purposes.

Article from the Hampshire Chronicle and General Advertiser, 23 May 1903, reproduced by permission of the Hampshire Record Office, ref TOP78/3/2

Other links: