Originally published on the Expatclic website under the pseudonym julianexpat with the title “An Englishman abroad” Letters home from the Peruvian Sierra 1873. Reproduced by permission of the author.

Julianexpat goes on a hunt into the Peruvian Andes for clues about a couple of Victorian Englishmen expats who came to the area in the 1870s, and who were decent enough to write home about it.

Table of Contents

Letters home from the Peruvian Sierra 1873

By boat to Peru

On October 13th 1873 a boat set sail from Liverpool destined for the port of Callao, Lima. The journey in those days tended to take upwards of fifty days, stopping as it did at such illustrious ports-of-call as Lisbon, Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo and Valparaiso. This particular boat, the Chimborazo, was carrying a passenger named Arthur Malcolm Heathcote. Arthur Heathcote was accompanying a friend, a Mr H.M. Gibbs, who had been advised to spend some time in the clear air of the Peruvian Sierra to recover from a lung complaint. Aside from choosing a mountain range on the other side of the world over, say, the Alps, what makes this particular intrepid Victorian adventurer more interesting is that he wrote more than 80 letters home in the time he was away. Those letters have stayed in his family to the present day, and when I came to Lima a couple of years ago I was given a copy of the letters by a friend to see if I could use them, or find out anything further about Arthur Heathcote and Gibbs’ adventure.

What was life like for a British expatriate in the wilds of altiplano Peru in the 1870s?

What impressions did he have of his host country, and indeed his host people?

What adventures befell the two of them in a landscape that had experienced no more transport advances than the lowly burro?

The boat journey as far as we can gather was uneventful until they turned the Cape and came face to face with the mighty Pacific. Passing another company ship in the Straits, the ambiguous message received was “strong breeze”. Arthur Heathcote recalls, with somewhat less ambivalence: “Tuesday night was the worst, one of the ship’s boats was smashed up, one sailor had his leg broken and another several ribs, and from the noise coming from the galley I am surprised that there is any crockery left”.

After a short stop at Valparaiso and a trip up to Santiago and Cauquenes in the Chilean Andes, they arrived in Callao aboard another ship, the Cordillera, on 19th December. Arthur Heathcote did not have much to say about Lima, as he was probably preparing for the daunting journey up into the Andes. There were mules to be bought and guides and arrieros (muleteers) to be found. A journey that today takes 4 or 5 hours in a car took for them 9 days by train and mule.

Life in the Peruvian Altiplano

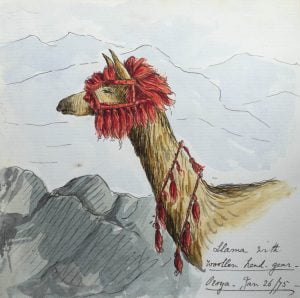

Oroya January 26 1875.

The intention was to stay in a town at the head of the Mantaro valley called Jauja, but after a month they decided that town life was not to their taste, and they looked to move to a small village down the valley named Matahuasi. There, they were able to enjoy the benefits of living quarters containing “more rooms than we have here, two patios, a good corral, and 2 gardens or orchards, one large and one small”.

Aside from one lengthy but spectacular sojourn over the mountains and down towards the jungle, they were to spend the rest of their time in the sierra in Matahuasi, and the majority of the letters describe their day-to-day life there, relations with the staff, dealing with an unfamiliar culture and, perhaps more amusingly, the ways in which they brought their own culture to Peru!

What strikes one most about the letters is how quintessentially “English” they are. They read a little like a Merchant-Ivory script or E.M. Forster novel. Arthur Heathcote and Gibbs were rooted firmly in the English gentry, had likely as not met at Oxford, and that tradition helped to colour their view of their surroundings, not to mention the things they got up to!

The daily routine is telling!

“From nine to half-past nine we do either Latin or Greek together and from half-past ten to one is our time for exercise, whether walking or riding out… at 2.30 we have a space for reading the papers; Gibbs gets the Guardian and Saturday Review. (one has to wonder??) Then we have an hour’s Spanish and an hour’s history and then spend half an hour pacing up and down our verandah learning by heart either Latin or Shakespeare. From then till dinner is time for letter writing”.

It seems unlikely that they maintained this schedule steadfastly and it was probably intended to smokescreen the parents back home, but the intention to entertain a routine at any level certainly strikes a chord with me.

In relations with the staff, Arthur Heathcote certainly seems to have been extremely affable, provided the running of the house went smoothly, almost to the extent of their being a part of the family. Any troublemakers were given short shrift however, and to the unfortunate first cook who “has proved to have a penchant for ‘aguardiante’ and this morning was as drunk as could be”, when he ended up “in prison for being drunk and disorderly and beating his wife last night” was given his marching orders. “This of course we can not stand, so we are going to send him packing and to get the best substitute we can”.

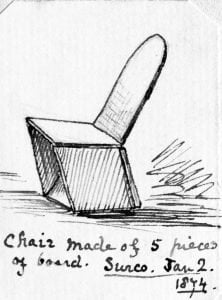

(Surco is a district of Lima)

They were not afraid of “mucking in”. Happy to go to market themselves, they frequently risked the derision of their staff.

“We ride over to Concepcion… with a baggage mule with large saddlebags of sacking in which to bring back the meat, and the other stores for the whole week… then plunge boldly into the mysteries of legs of beef, halves of sheep and ‘lomo’. The usual result is that we are well taken down and the cook laughs at us unmercifully when we exhibit our purchases”.

Apparently they made most of their furniture themselves from wine boxes, made their own curtains and set up a “fowl yard” with nesting boxes also made out of wine boxes.

They seem to have taken an interest in the local culture, with frequent visits to the local “big smoke”, Huancayo and other villages thereabouts to check out and buy local vicuña textiles at the Sunday morning markets. Interested in the local culture as they were, Heathcote drew the line at bull-fighting. Matahuasi still has its bull-ring, and Heathcote does make comment: “As practised here, this barbarous amusement is truly sickening”

Regarding English eccentricities, aside from the butterfly catching and shooting expeditions, it is likely that Arthur Heathcote and Gibbs’ most startling pastime to the local population was their love of amateur dramatics. In their audiences they included not only friends but also the household staff. Their first evening of entertainment, complete with painted scenery, theatrical wardrobe and lighting “was an eminent success and puzzled them all tremendously, indeed one of the sisters was quite frightened at first.”

From the letters, it would seem that the two of them spent most of the rest of their time in Matahuasi putting on plays. Once the news spread to the surrounding area of their success; “quite nice little party, and all enchanted. They had never seen anything of the kind, and the scenery, the dresses and the dancing quite transported them”, they seem to have struggled to keep people from the door! “We found it necessary to keep the front gates locked for there was quite a crowd clamouring for admission”.

But even at this stage, they were missing the piece de resistance. They had ordered a piano to be brought up from Lima by mule to add a final touch to the performances. It eventually arrived about two months before they were due to leave.

“The evening was most enlivened by the piano. Doña Jesusa can play, although it is with a hand of iron and a touch of wood, but knows more things than we expected… afterwards we cleared the room with a view to some dancing and managed a mazurka very fairly, though Doña Jesusa’s time was fearful!”

Following Heathcote’s footsteps

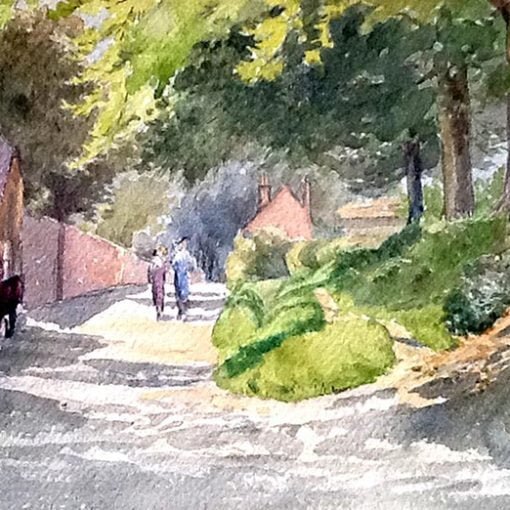

A couple of weeks ago, I finally followed Arthur Heathcote and Gibbs’ steps as much as is possible in a car. The jaw-droppingly spectacular route up to the Sierra from Lima now follows the rail line all the way to Matahuasi, although in 1873 it only reached about 70 kilometres from Lima. The Mantaro valley is quite beautiful. The countryside is a lush green and rolls gently, not unlike the Yorkshire Dales at times, albeit about 3500 metres higher up! It is clear that the land is very fertile, with fruit trees and fields of artichokes everywhere.

My aim, aside from getting a clearer picture of the Mantaro Valley, was to visit Jauja, find Matahuasi, and see if I could find anyone who might have records of foreigners who had stayed in the area. In the event, I tracked down (literally – in the back streets!) the current Mayoress of Matahuasi, Gloria. In the course of our conversation, and at mention of a piano, Gloria suggested we meet up in the local church, where we found… a very old organ from Augustusburg in Germany. Now I’m not willing to make the leap, as I can distinguish piano from organ, but I did think I ought to include it as a detail. It would be nice to think that Heathcote and Gibbs’ “piano” remained behind when they returned to England.

All in all, I suspect that Arthur Heathcote made quite a success of his expatriate experience. In the first place, one could not have been too “precious” to have made such a journey at that time. Having now taken the journey myself in the comfort of a car, I can see that to reach Matahuasi from Lima, let alone originally from Liverpool would not have been for the faint-hearted. He was keen to learn Spanish and did so within five months of arriving in the Sierra. He even learned a little Quechua. He brought something of his own culture to his temporary home, and enjoyed much of what his host nation had to offer. Who knows, I’d even like to think he left something up in Matahuasi that is used by the locals even today!

Julian Davies

Lima, Peru

April 2008

Editor’s Notes and Links

- This article was originally published on the Expatclic website under the pseudonym julianexpat and with the title “An Englishman abroad”. Letters home from the Peruvian Sierra 1873.

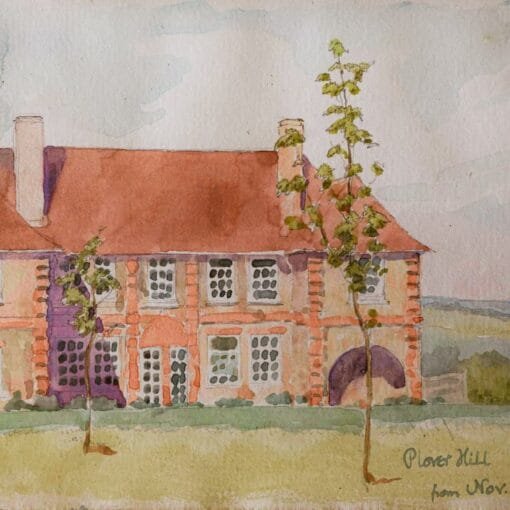

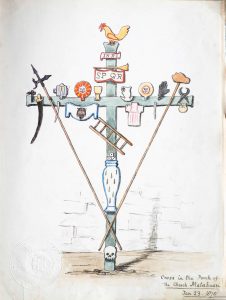

We are very grateful to the author, Julian Davies, who has very kindly given permission for us to reproduce it here. The text and photographs are unaltered from the original version apart from the addition of subheadings. Thanks to the great-great-grandson of Arthur Heathcote, we have been able to include copies of AMH’s original drawings.

- The author surmised that Arthur Heathcote and H.M.Gibbs may have met at Oxford. Heathcote had, like his father, gone to Oriel College, Oxford. Henry Martin Gibbs had been educated at Lancing College in Sussex and Clare College Cambridge. He was three years younger than Arthur Heathcote. Despite the health problems cited as the reason for the trip to Peru, he would go on to become High Sheriff of Somerset and live until just before his 78th birthday. He was a significant benefactor of Lancing School, where there is now a house named after him.

A.M.Heathcote’s obituary in the Hampshire Chronicle reported that

- It is said that in his younger years he was very delicate. [After Oxford he] read for the bar for a short time, but became a schoolmaster for some year, first as an assistant master at Lancing under Dr. Sanderson.

The three year difference in age between AMH and HMG means that they were unlikely to have overlapped at Lancing.

The link between them could well have been through their parents and the Oxford Movement which reinvigorated the Anglican church in the mid to late 19th century. John Keble had been Sir William Heathcote’s tutor at Oriel. In 1835 Sir William persuaded John Keble to come to Hursley as Vicar, where Keble used the proceeds of his best-selling book of poems for Sundays, “The Christian Year“, to fund a substantial rebuild of Hursley Church.

H.M.Gibbs’ mother Blanche was a cousin of novelist Charlotte M. Yonge who lived in Otterbourne. Charlotte Yonge was much influenced by Keble and has been called “the novelist of the Oxford Movement”. She was well-known to Sir William Heathcote, who admired her writings.

After Keble’s death in 1866, both Sir William Heathcote and William Gibbs were involved in plans to create Keble College Oxford in his memory. William Gibbs had become the richest non-noble man in England thanks to his South American guano business and donated the funds for the Keble College Chapel. He did not live to see the completion of the chapel, but H.M.Gibbs, returned from Peru, took part with his elder brother Antony in the opening service on St. Mark’s Day 1876, conducted by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

- The Pacific Steam Navigation Company

- The PSNC had opened a service from Valparaiso to Callao (Peru) in 1840. In 1873 they started a weekly service from Liverpool to Valparaiso, having ordered several new ships for the route. The weekly service quickly proved overambitious. 1874 the service was reduced to fortnightly, leaving the company with 11 ships laid-up in Liverpool. In 1878 the Orient Line took over four of the laid-up ships, including the Chimborazo, for use on the Australian route.

- In March 1878 the Chimborazo had a dramatic collision with the New South Wales coast at Point Perpendicular, south of Sydney. Thanks to its compartmentalised construction, the ship survived. It was quickly repaired, and was scrapped in 1897.

- Screw Steamer CHIMBORAZO built by John Elder & Co

- Screw Steamer CORDILLERA built by Randolph, Elder & Co.

- Screw Steamer GALICIA built by Robert Napier & Sons in 1873 for Pacific Steam Navigation Company, Liverpool

- Arthur Heathcote and H.M.Gibbs travelled home on the Galicia in 1875, arriving a few days after the death of Gibbs’ father William Gibbs (3 April 1875).