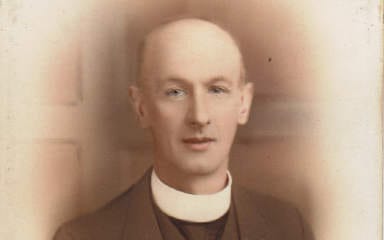

The Reverend Philip Barrett, MA, BD, LLM, FSA, FRHistS

Rector of Compton and Otterbourne 1978 – 1998

Reprinted from the Compton & Shawford Parish Magazine, June 1998

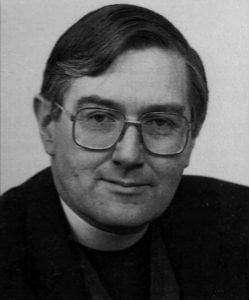

For those who were unable to join the large congregation which filled the nave of the Cathedral on 1st May, St Philip’s Day, for the impressive Requiem Eucharist for Philip Barrett, presided over by the Bishop of Winchester, there follows the text of the sermon preached by his longstanding friend Geoffrey Rowell, Bishop of Basingstoke:-

Of the four references in St John’s Gospel to the apostle Philip, whose day this is, three relate to sight – the words of Philip to Nathaniel about Jesus; the words of the Greeks who came to Philip and told him they would like to see Jesus; and Jesus’ own words to Philip who asked him if he might see the Father, Anyone who has seen me, has seen the Father. Our Christian faith is international, and that means it is inescapably personal. The living Word of God is made flesh, and we see and know what God is like in and through Jesus in whom we behold the glory of the Father, full of grace and truth. And those who are called into the way of discipleship are those who are called to Come and see, to live so closely with the one who calls them that they live in him and he in them. And those whom the Lord calls to ordained ministry, to be priests in his church, are those who in special way are called to embody and enable that closeness to Christ. As John Keble wrote in one of his poems for the Christian Year:

So glorious let thy pastors shine

That by their speaking lives the world may learn.

It is by faithful lives – ‘speaking lives’ as Keble calls them – that Christ is known: in the biddenness of prayer, in the ministry of the pastor to whom is given the cure of souls, in the reverent ordering of worship, and in the study of Christian truth. Because the pastor is the one who is called to embody the love of Christ, the truly pastoral is the true embodiment of Christian mission, they belong together. Just as to have seen Christ is to have seen the Father, in the same way those called and ordained to serve as priests are those in whom Christ’s care, Christ’s love and Christ’s truth may be seen and known.

Today, on this St Philip’s day, we come to bid farewell, to commend to God, and to give thanks for another Philip, priest, scholar and pastor. Philip Barrett was named after another great priest, Philip Duke-Baker, and I preach today not just as bishop but as a friend of some thirty years, from the time when we first met at Cuddesdon in the last years of Robert Runcie’s time as principal. His roots were in Portsmouth where he was first a chorister and then a lay-clerk of Portsmouth cathedral, and where he was educated at Portsmouth Grammar School. The devotion and discipline of his family (his father was a naval officer) gave so much to him, and the seeds of his vocation it seems may have been sown when he was taken at the time of his grandmother’s death, to see her body. He went up to Exeter College, Oxford, in 1965 where he was a pupil of Eric Kemp to whom he owed a great debt. He dedicated his major book to Bishop Eric with affection and gratitude, noting that ‘his example, teaching, encouragement and friendship’ had been a major influence in his life. It is a sadness that Bishop Eric is unable to be with us today, as I know he would have wanted to have been.

He served his title as curate at Pershore Abbey under Christopher Campling, and then a brief second curacy in this diocese at St Peter’s, Bournemouth, before going in 1976 to Hereford Cathedral as a Vicar Choral. His ordered mind and liturgical and musical sensitivity made him invaluable in the ordering of the cathedral services, as liturgical adviser to the Bishop of Hereford, and as chairman of the Diocesan Liturgical Committee. He worked with the cathedral library and the Hereford Diocesan Advisory Committee, and his musical abilities, both practical and theoretical, were put at the service of the Three Choirs Festival. His expertise and detailed knowledge of cathedral music was often drawn upon by church musicians and cathedral organists, many of whom have written to say what a loss his death is to them personally. In 1986, he came back to this diocese as Vicar of Otterbourne, and a year later as Rector of the United Benefice of Compton and Otterbourne.

Philip would have been the first to acknowledge that he was more naturally at home in a cathedral than in a parish, but because his primary sense of vocation was as a Christian priest, that meant that he was concerned to do his very best by and for his parish. There are many who will testify to his pastoral care, the ordering of worship, and his endeavour to pass on his sense of Anglican tradition. At the end of his study of the nineteenth-century cathedral, reflecting on the specialist experience that could be carried from one cathedral to another, he wrote that it might ‘also he possible to regard a vocation to collegiate life as equally valid as a vocation to monastic life or the parochial ministry’ – a view that Archbishop Benson had argued for in the last century.

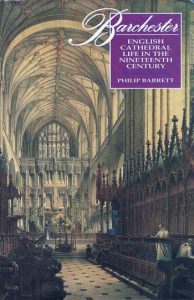

by Barrett, Philip

Published by Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1993

Philip Barrett was a considerable scholar, who wore his learning lightly. I still remember examining his Oxford BD thesis, (appropriately sitting round John Keble’s dining room table in the Senior Common Room of Keble College). The published version of that thesis, still available under the simple title Barchester, is marvellous mosaic in which everything from service sheets to vergers’ records and the quirks of canons is pressed into the service of the best account of Victorian cathedral life that we are ever likely to have. Philip had a wonderful sense of humour and an eye for the ridiculous, and his historical writing gave him a great opportunity for the amusing anecdote. He would have been glad that his funeral here today is not like that of Francis Kilvert’s aunt in Worcester Cathedral, where the bearers covered by a pall could not see where they were going, or the minimalist installation of Dean Gregory at St Paul’s, when he was placed in a chair by the light of a wax taper carried by a verger in a tin kitchen candlestick. He wrote chapters for the books on Winchester and Chichester cathedrals, and two chapters are still to appear for the forthcoming history of Hereford. Add to these works on organs and organists in Portsmouth and on English cathedral choirs and it is an impressive achievement. The more so because this quiet, patient, scholarly work was done as part of his vocation as a priest and alongside the manifold pastoral and administrative concerns.

Church musician, church historian, and also church lawyer, for law was a life-long interest and particularly ecclesiastical law, which he crowned with a Master of Laws degree in canon law at Cardiff in 1994. And then there was cricket – an abiding interest, and it is good to welcome at least one distinguished cricketer here today from the West Indies. Philip would have been pleased. Add to this travelling in France and steam railways – that perennial hobby of the clergy, and you have a picture of Philip’s many interests.

Although it is natural for us to think of how much more Philip might have given in scholarship and in pastoral care, his measured, even devotion and sense of priestly vocation, would surely have led him to remind us that our days are in the hands of God, who gave us life and to whom we return at the end. His mother, Angela, to whom with all his family and close friends the prayers of our hearts go out today, told me just this morning that one of Philip’s favourite texts was from Psalm 37, which begins Fret not thyself. He may well have found that so sustaining because it is the theme of one of Michael Ramsey’s outstanding addresses in his ordination charges, The Christian Priest Today. We live, as Ramsey reminds us, in a fretting world and the gospel can be paraphrased, ‘Fret not, only believe. ‘Dwell in the land and verily thou shalt be fed. ‘Remember your inheritance, the Catholic Church of the ages, the country of the saints. Claim this as your own country, and go on living in it. Philip surely did, and knew also the truth of the verse that comes towards the end of the psalm. Keep innocence, and take heed unto the thing that is right. for that shall bring a man peace at the last. Philip’s determination, his quiet stability, his wise sense of balance and perspective, his learning, his music, his acceptance of the limitations of ill-health, made up his ‘speaking life’. Almost his last words were to ask for his favourite honey sandwiches, but in the Promised Land flowing with milk and honey we taste how gracious the Lord is:

Jesus dulcis memoria

Dans vera cordi gaudia

Sed super mel et omnia

Eius dulcis praesentia.

But sweeter than the honey far, the glimpses of His presence are – but surely now not just the glimpses, but the fullness of Christ’s light and glory to whom we commit our beloved brother Philip. And the Lord whom he served surely says to him, Come and see! Behold the vision of my glory, enter into my Easter joy.

+GEOFFREY BASINGSTOKE