Table of Contents

Compton Clergy of Long Ago

Introduction

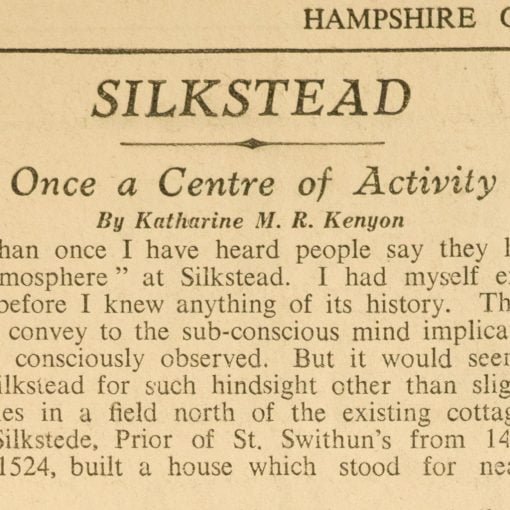

“Compton Clergy of Long Ago”, by J.S.Drew, appeared in the Compton Parish Magazine over the first nine months of 1934, with an update on Philip Williams added in October 1935.

We are indebted to the Hampshire Records Office, who retain copies of most past issues since 1928 in their archive (under reference 1M76/PZ)

Magazines supplied to the Records Office at that time were bound together covering the years 1934-36. Unfortunately, there must have been an error in the binding process, because article 5 of the series is missing all but the first few paragraphs. See “Editor’s note” below.

Part 1 January 1934

By the North Door of our Church hangs, in a frame, a list of 51 Rectors of Compton from 1288 onwards.

North Door of our Church hangs, in a frame, a list of 51 Rectors of Compton from 1288 onwards.

Memories of those of them who laboured here during the last hundred years still remain among some of our older people; but what of their predecessors? Their names, once so well known here, are completely forgotten and all the traces they have left are a few entries in old Church books, a few signatures on faded documents, a few allusions in diocesan records and so forth.

Yet it is intriguing to gather together what is to be found about our clergy of olden days for they were an interesting and varied lot of men. As we glance at this aspect of the history of our parish we shall meet devoted parish priests who gave all their best to Compton Church and its people, rich pluralists, men who doubled the roles of priest and farmer, schoolmasters, men destined to be bishops, well-known scholars, an ex-monk and — it must be admitted — men whose connection with Compton was a purely financial one, who took the emoluments of the living and left the duties to be performed by underpaid curates.

And yet, scandalous as this appears to us now, we should be wrong to judge the Rectors of this last type too severely. They lived in times when the spiritual life of the Church was at a low ebb, and the system they practiced was almost universally regarded as legitimate.

We shall meet their curates too, and here the types are not so varied. Often the clever sons of impoverished families, lacking the influential backing which led to preferment, regarded socially as of not much account, most of them could look forward to little but a life of genteel poverty which only a great Faith could make tolerable. The nature of their ministry, judged by present-day standards, may not have been an exacting one, but it was they who, in days of religious torpor, kept the Church’s banner flying here, and we cannot doubt that the religious tradition of Compton owes them much. Let us give them a kindly thought as we pass on.

In our hunt for the clergy of the pre-reformation period the scent is almost always extremely poor. Our usual coverts — court rolls and the like — so productive where laymen are concerned, seldom hold a priest. The reason is that a mediaeval layman’s history, as far as it can be recovered now, is based on the land he held and the offences he committed. The parish clergy seldom held land (apart of course from glebe) and their offences, if any, were dealt with by ecclesiastical courts. The bishops’ registers give details of each rector’s appointment, but that provides us only with a bare list of names.

This is a great pity, for the history of the Church in Compton during the long centuries of the Middle Ages must contain, did we but know it, the stories of many devoted men who found in the days of plague, pestilence and famine many opportunities of witnessing to the Faith and of serving their flocks.

One interesting sidelight we do get from the Manor Court Rolls. After the Black Death in 1349 when, as we have seen elsewhere, it is probable that at least a third of the Compton folk died, numbers of the small 16-acre holdings were derelict by reason of the death of those who had farmed them and the absence of any new tenants who could take them over. To prevent land, brought into cultivation with such toil, from reverting to jungle, the parish clergy seem to have been permitted, if not encouraged, to take over holdings and to farm them themselves. This they were well fitted to do. The majority of the clergy of the period were born on the land, their early years were spent in helping their fathers, and they were thoroughly familiar with the practical details of agriculture.

At all events, here in Compton, during the 50 years which followed the Black Death, three rectors — John de Kymberle, Michael Donheved and Thomas Tyny — all held land from the Priory of St. Swithun on exactly the same terms, as to rent and services, as their parishioners. This state of affairs seems to have occurred in Compton neither before nor since.

One other incident we may note as we pass on, although it concerns a cleric not officially connected with our parish. In 1318 one Adam Canep, a clerk in holy orders, was committed to the Bishop’s Prison for (among other offences) stealing two sheep at Compton. Now the Canep family had for many years kept a tavern in Otterbourne and, not long before Adam’s fall, Matilda of that name had been fined for “breaking the Assize of Ale,” which usually means adulterating the beer or giving short measure. So it may be that, like his more famous namesake, this Adam was beguiled into evil courses by a woman.

Part 2 February 1934

A.D. 1530 and the eve of the Reformation. One wonders whether our Compton friends, the Philpotts, the Whytemans, the Martins and the rest of them had the slightest suspicion of the coming storm. Probably not, for although people at the heart of things in England and elsewhere perceived very clearly that new, dynamic and incalculable forces had arisen, yet these things were hidden from the man in the street, whose time and attention were, indeed, very fully occupied with the earning of his daily bread. And how permanent, when he did think about it, must have seemed to him the Religion in which he had been born, which took charge of him from the cradle to the grave and which was the life-blood and the driving-power of the society of his Age.

Yet, to those who could look beneath the surface, that tremendous Pageant, which was the Mediaeval Church, was showing undeniable signs of decay. It was not that “the Faith once delivered to the Saints” had been forgotten, nor that devout men and women were lacking, but rather that the Church was carrying among its clergy an altogether undue proportion of “passengers.” Most Churches, indeed, have included a certain number of idlers, of sceptics and of humbugs, and, when the percentage is a small one, no great harm is done. But there seems to be an undefined line beyond which it is perilous to go, and that limit had certainly been passed in 1530.

And so it came about that the true Father-in-God, the devoted parish-priest, the saintly men and women of the cloister, the friar in whose heart still burned the zeal of St. Francis — though they were possibly still in the majority — were half hidden by a crowd of worldling prelates, of pluralist rectors, of idle chantry-priests and of all that miscellaneous collection of redundant clerics whose lives seldom edify and sometimes scandalize the student. It was the daily spectacle of these men, with the debasement of their life and doctrine, rather than any question of high politics or Protestant zeal, which alienated the average Englishman from the Old Church.

With this background in our minds let us consider more closely the position of the Church in Compton in these critical years.

Mr. David Sybald had been Rector since about 1516 and it chances that a document, which throws light on the type of man he was, has come down to us, and that in rather a strange manner. When Thomas Cromwell was sent to the scaffold his private papers were seized, and among them was found a letter, dated March, 1535, asking for instructions as to the disposal of money left by “the parson of Compton” (David Sybald) to the Observants, and impounded when that order was suppressed.

Now the Observants were a branch of the Franciscans, small in numbers but very strict in practice, who based their lives on the primitive rule of St. Francis and held in abhorrence the clerical abuses to which reference has been made. There were only seven houses in England and one of these was at Southampton. When the question of Henry VIII’s divorce came to the front, and others were considering on which side of their bread lay the most butter, the Observants refused to make the smallest concession to royal lust, and suffered in consequence the full weight of royal anger. The order was instantly suppressed (five years before the general dissolution of the monasteries) and several of their leaders suffered martyrdom.

Such were the people to whom David Sybald left his money, and in so doing showed on which side his own sympathies lay. Indeed to make such a will at all, in Henry VIII’s reign, argues very real conviction and a good deal of moral courage.

It may be safely inferred therefore that in our old Church here during these difficult years the Catholic Faith was preached in purity and love, and that, in the last days of obedience to Rome, it was the best side of Romanism which Compton people saw.

Of David Sybald himself, when one considers the gentle spirit of St. Francis and the extent to which his teaching permeated the Observants, one wonders if it is stretching the art of deduction too far to suggest that of this Rector of Compton too it may be true to say

…Christes lore, and His apostles twelve He taught, but first he folwed it himselve.

Part 3 March 1934

David Sybald died in 1534, and (after the brief rectorate of William Philpott, a member of the Compton family of that name) was succeeded in 1536 by Anthony Barker. This rector was here for 15 years and as, during his time, practically the whole of the Reformation changes — in so far as they effected the average Parish Church — were carried out, it is not too much to say that his incumbency covered the most momentous period which Compton Church has seen. Mr. Barker was also closely connected with Winchester Cathedral, and it is necessary therefore to glance for a moment at the changes which were taking place there at this time.

The Benedictines of St. Swithun’s, under their Prior William Basing, were in 1538 faced with the dilemma which was confronting all the religious houses. Should they (recognising that the King seemed determined to get possession of their endowments) surrender voluntarily, trusting that royal clemency would preserve to them something out of the wreck? Or should they attempt a resistance which might — and in some cases did — lead straight to the gallows?

Prior Basing and the Brethren chose the former alternative and, financially, had no reason to regret their decision. The Priory was dissolved but in its place the Chapter of Winchester Cathedral was constituted, and to this body was handed over practically the whole of the Priory endowments. Among the original personnel of this new Capitular body were two rectors of Compton, our friend Anthony Barker (who was appointed a Prebendary with a stipend of £31/11/8) and John Erle, whom we shall meet later. Incidentally we may note that Prior Basing became the first Dean and, resuming his family name, reappears in history as Dean Kingsmill.

We cannot tell whether the Cathedral or Compton made the greater claim on Mr. Barker’s attention, but there was certainly a curate — one Walter Welche — here in 1541.

It was during the last four years of Anthony Barker’s time here that the great devastation of Churches took place. It must be remembered that in the Middle Ages the English Parish Churches were famous throughout Christendom for the beauty and splendour of their decorations and fittings. The piety of successive generations had collected within their walls the best works of contemporary art, whether of the painter, the glass-worker, the sculptor, the broderer, the wood-carver or the silversmith. An English chancel must have presented, from an artistic point of view, a scene of great beauty, and it is unlikely that Compton (the home of the rich and devout Philpott family) fell below the general standard.

By order of the extremist advisers of Edward VI an almost clean sweep was made of wall-paintings, stained-glass windows, carved figures, altar needlework, etc., and we can only guess at the loss, in terms of works of art, which our own Church suffered at the hands of the wielders of the crowbar, the hammer and the whitewash-pot.

Anthony Barker died in 1551 and was succeeded by John Erle. This rector had been a monk at St. Swithun’s at the time of the dissolution of the Priory and, on the formation of the new Chapter, had been appointed a ‘Petycanon to synge in the Quere’ at a stipend of £10. He was also private chaplain to Dean Kingsmill who left him by will “one fethor bedd and boltster and one coverlett and one of the best vestments in my Chappel.”

His incumbency of Compton was a time of kaleidoscopic changes. For the first two years the Protestants were supreme, then, during the five years of Queen Mary’s reign, Roman Catholicism was re-established, only to be overthrown finally on the accession of Queen Elizabeth. The regime of Queen Mary seems to have been more acceptable to John Erle than that of his sister, for one authority states that “in the first years of Queen Elizabeth the rector of Compton was deprived for refusing to take the oath of Supremacy.” If this is so, it undoubtedly refers to John Erle who disappears from our ken in 1559.

Part 4 April 1934

The reigns of Elizabeth and James I, which we have now to consider, must have made it clear to Compton people that, whatever reforms the Reformation had effected, the abolition of absentee and pluralist clergy was not one of them. During the 76 years which elapsed between 1560 and 1636 there were seven rectors of Compton, and six of these were undoubtedly non-resident. It seems to have been customary ‘to present to our benefice cathedral and other dignitaries, they being expected to provide a curate to perform the pastoral duties of the parish. As there was a wide gap between the income of the benefice and the stipend of a curate, it is not difficult to see the grave abuses to which the system gave rise.

Four of the rectors during this period were prebendaries or canons of Winchester Cathedral and, in their cases, the Statutes of Henry VIII for the regulation of the Capitular body give us an indication of their position in the matter. Each prebendary was provided with a house adjacent to the Cathedral (many of the monastic buildings of the old Priory were still standing) and there he was bound to reside. Rules. were also laid down for his attendance at the Cathedral services. He was allowed 8o days leave each year for the purpose of visiting his benefices or attending to his private affairs. It was therefore entirely a matter for the rector’s conscience. If he were an earnest faithful man he was able to exercise a general supervision of the parish. If, on the other hand, he had other interests, there was nothing to prevent his staying away altogether, and the literature of the period suggests that this second type was very far from rare. Of course, the more other appointments a rector held, the less would Compton be likely to see of him.

Taking these rectors individually we find that David Padye (1560-1562) and Thomas Odin (1562-1566) were both prebendaries of Winchester and were followed by Edward (or Edmund) Walker who was here for eight years. Very little is known of the last except that, during his incumbency of Compton, he held no other benefice so that it is probable that he actually lived here.

In 1574 there appears on the scene Dr. Robert Raynolds, of whose somewhat chequered career we have fuller information. Apart from parochial benefices he was a Canon of Lincoln and of Winchester and had been Commissary to the Bishop of Winchester and Master of St. Cross. During his tenure of this last position he contrived to lease away a considerable portion of the Hospital lands and even some of the actual buildings — to the great detriment of the inmates. Special legislation had to be passed to annul these transactions and he himself was ejected from the Mastership. He evidently made his peace with the authorities very quickly for we find him receiving other preferment shortly after. He remained rector of Compton until his death in 1595, when he was succeeded by Dr. John Harmer.

This very learned man was rector of Compton from 1595 until 1613. During the whole of this time he was either Headmaster or Warden of Winchester College and Rector of Droxford. Furthermore he must have been very fully occupied during the years 1607-1611 with the Authorised Version of the Bible, of which he was one of the translators. It may be assumed that the bulk of the work in Compton fell on the curate, John Taylor.

On Dr. Harmer’s death in 1613 he was succeeded by Abraham Browne of whom we have little information except that he was Prebendary of Winchester and retained the benefice until his death in 1627.

His successor was Dr. James Wedderburn, a native of Dundee, in whose hands pluralism had become a fine art. It is not suggested that he is the only Scotsman who has perceived the financial possibilities of England, but certainly he created a record in Compton. Simultaneously with his rectorate here — and until 1636 when he returned to his native land as Bishop of Dunblane — he held the positions of Prebendary of Ely, Prebendary of Wells, Vicar of Fulbourne, Cambridgeshire, and Vicar of Mildenhall, Suffolk. The work in Compton was performed by his curate, William White, and it would be interesting to know what salary the latter received from this very canny Scot.

Part 5 May 1934

Dr. Wedderburn was followed by another record-maker — this time for the briefness of his stay in Compton. John Ramsey was rector for a few weeks only and then exchanged livings with the rector of Mersham, Kent.

The latter, Thomas Hackett, was a man of the country-gentleman-parson type and he lived in stirring times. He came to Compton in 1636, when the stage was already being set for the drama of the Civil War, he saw the siege of Winchester Castle, he saw the Parliament’s soldiers billetted in our village, he was here right through the Commonwealth period and he lived here long enough to see Charles II firmly established on the throne.

For the Church of England it was a time of recurring crises, comparable only to the*** upheavals caused during the Reformation.

Thomas Hackett was a well-off man and had a house near Winchester College, the Warden of which was his brother-in-law, but he also lived at Compton Parsonage and was perhaps the first resident rector since the Reformation.

In Compton, he held on lease the 2 virgates and the 5 acres formerly held by Carpenter and Symmes respectively, but whether he farmed himself or was an intermediate landlord, cannot be said. The religious troubles of the time passed him by and, while Anglican clergy were being thrown out of their livings right and left, this rector remained undisturbed at Compton.

How much of this immunity he owed to his own amiable qualities, how much to theological adaptability, and how much to the fact that he was nephew to a Lord Mayor of London, is, happily, not for the present writer to estimate. He died in 1661 and is buried in the chancel of the old nave.

After his death, John Holloway was appointed to the rectory of Compton. He held the benefice for under eight months and nothing is known of him.

Very little is known of his successor as rector, James Morecroft, who remained here until his death in 1667 and is buried in the chancel of the old nave.

In 1667 Dr. William Burt became rector of Compton after the death of James Morecroft.

Dr. Burt was Warden of Winchester College and a prebendary of Winchester. He had been a warm supporter of the Parliament during the Commonwealth period, but on the return of Charles II he transferred his allegiance to that monarch with such enthusiasm that he even journeyed to London in order to present a loyal address.

Such a signal proof of devotion could hardly fail to evoke some tangible mark of Royal favour, and Dr. Burt was rewarded with the rectories of Nursling and of Ashe in Surrey.

John Barton is mentioned as his curate in Compton.

The Recusancy Acts, first introduced during the reign of Elizabeth I, had remained in force throughout this period, although they were temporarily repealed during the Interregnum (1649–1660). Local records list several notable “Recusants” who remained loyal to the pope and to the Roman Catholic Church and were fined for not attending Church of England services.

In 1676, each parish in the Province of Canterbury was called upon to return the number of inhabitants, of 16 years or over, in three classes according to their religious denomination. The churchwardens of Compton reported 92 Conformists, 14 Papists and no Non-conformists.

Part 6 June 1934

Although John Barton’s incumbency lasted only 6 years (1677-83) it is a memorable one for Compton archives because it was he who began to record the burials in our parish. The parochial clergy had been enjoined 140 years earlier to keep a register of all baptisms, marriages and burials in their respective Churches, but in many parishes the order had been consistently ignored, and, unhappily, our own parish seems to have been among the number. At all events Mr. Barton provided himself with a book which he headed “An account of ye Burials in ye Parish of Compton since ye Act for burying in woollen, bearing date 1st August, 1678.” It is rather pathetic to note that among the first few entries he had to make were those of his own wife and baby. Mr. Barton also initiated the admirable practice of entering in his book detailed lists of subscribers to various outside Funds such as the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral, the ransoming of English captives in Algiers, the relief of French Protestants and so forth, by which means valuable lists of Compton inhabitants have come down to us. Mr. Barton died in 1683.

His successor, John Webb, was rector here for 38 years (1683-1721) and he too was evidently resident in Compton. Indeed, save for one or two short periods we shall notice later, we have seen the last of absentee rectors. In 1695 a son was born to Mr. and Mrs. Webb and, in his paternal enthusiasm and most fortunately for Compton records, the rector decided to signalize the occasion by starting a Baptismal Register, in which, by the way, for the next few years the little Webbs make a brave show. He began our Marriage Register in 1696.

It is interesting to note that it was during this time that Roman Catholicism died out in Compton. Over 150 years had elapsed since the Reformation and, in spite of penal legislation and savage fines, a few Catholic families had so far retained their Faith (there is a curious allusion to “ye papists’ Burying Place” in our Register of 1679). Their position was however one of great difficulty and increasing poverty and the “14 papists of 16 years and over” whom our Churchwardens had reported in 1676 had, by 1725, become “Papists, — none.”

Mr. Webb left Compton in 1721 and was succeeded by a mysterious person, John Thistlethwaite, of whom little is known except that he was a Canon of Chichester. The latter died in 1724 and was followed by a very notable Compton character, Charles Scott (1724-62).

Mr. Scott was 47 when he came here. He was a man of some means, possessing an estate in Essex and his first act here (after giving 5/- to “ye bellringers” and expending 29/2 on candlesticks, glasses and mugs) was to set about building a new rectory. This raises the question as to where the Compton rectors had lived hitherto, but it is not safe in the present state of our knowledge to say more than that the “Compton Parsonage” of Thomas Hackett’s time was almost certainly either the house now occupied by Mr. Penny or one standing on the site of the present rectory. How the rectory as we know it now was originally planned and how or when it was enlarged is beyond the scope of these notes, but in his first two years here Mr. Scott spent £533 (a large sum in those days) on the building, as well as very considerable sums later on the house, garden and barn.

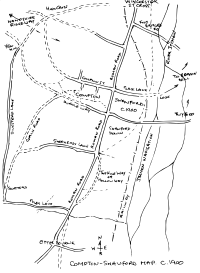

An interesting, if somewhat negative, account of the parish as seen by its rector was furnished by Mr. Scott to his Bishop in 1725. He estimates the population at 130 souls (including 2 “Protestant dissenters”). Mr. William Harvey is his curate. There are no chapels, no papists, no resident of note (rather a nasty knock, this, at Mr. Harris of Silkstead) and no school. It is to be remembered also that there were no week-day services, very few celebrations of the Sacrament, no Sunday School, none of those parish organizations which we take nowadays as a matter of course and none of the large correspondence which falls to a modern clergyman’s lot. The needs of the parish were considered to be adequately met by a service on Sunday morning, another in the afternoon, a celebration of the Holy Communion about four times a year and pastoral visits to the 20-25 families which composed this cure of souls.

What manner of man was it then who, to cope with these modest duties, found the assistance of a curate necessary? In our next article Mr. Scott’s own account book will help us to picture this parson of the “good old days.”

Part 7 July 1934

The editors of “Parish Registers and Parochial Documents” (Winchester, 1909) describe the book started by Mr. Scott as the “Compton churchwarden’s accounts” — which it most certainly is not. It contains, in fact, a mixture of the rector’s church and personal accounts, from which are excluded, as far as one can see, only the cost of his food, his clothes and the wages of his servants. He is obviously not a skilled accountant and his book should be regarded rather as a “human document” than as a hand-book for financial purists.

The credit side consists almost entirely of receipts from tythe, which varied between £120 and £165 a year. These were usually paid about nine months after they became due, but during “ye bad times” of 1742-6 several of the Compton farmers got into difficulties and gave the rector promissory notes for the amount of their debts. On more than one occasion at this time he made — an all round abatement of about 2 per cent., and to one farmer who went completely “broke” he made a present of five guineas.

Of his expenses, apart from taxes and the building and upkeep of the rectory, the chief items are the stipends of the curates, William Harvey (1724-30), Thomas Palmer (1730-34), William (?) Preston (1734-40) and Dr. Robert Shipman (1740-65). It is rather surprising to find that the services of a Doctor of Divinity could be secured for £34 a year. We may note, in passing, that it was the curates who kept the Parish Registers.

The rector spends much time and money on his garden and often buys fruit and other trees. He reconstructs the paths and purchases for that purpose no less than 45 loads of gravel, a “rolling-stone” and box plants for the edging. He keeps a horse, of course, and does a little farming in a small way on extra land which he rents. He does not disdain the profits which accrue from the petits métiers for, when his pigeon-house needs cleaning out, he pays a man 6/6 for doing it, packs the proceeds of the cleaning into sacks and sells it for 18/9. There is no doubt that all these interests fill a large place in his life, but the death of a gardener discloses the fact that that functionary’s wages are a year in -arrears.

It is not possible here to refer to more than one or two of his indoor expenses. The amount of beer bought or brewed at home seems sometimes rather large but then the XVIIIth was notoriously a thirsty century. That the rector was not unreceptive of fresh ideas may be inferred from the fact that when a new-fangled drink called “tea” penetrates at length to Compton he hastens to provide himself (at a cost of £4/3/6) with “a Tea Table, a sett of china and a sett of tea spoons.”

His relations with his tythe tenants have already been noted. In his dealings with his poorer parishioners he appears in a less attractive light. It was a period of widespread poverty and many cases of need must have come to his knowledge in Compton, yet, after a shortlived spasm of comparative generosity when he first came to the parish, he stabilizes his benefactions at 2/6 to “ye poor” each Christmas and very occasionally an odd guinea. On the rare occasions when the parish bounds are perambulated the rector apparently dispenses free refreshment.

But what is most startling is that during all these 38 years the Church is referred to only four times. In 1728 Mr. Scott gives 10/6 towards casting a new bell, in 1731 £2/2/0 towards “building a Gallery in ye Church,” in 1745 £4/4/0 “towards ye alteration of ye reading-desk and Pulpit” and in 1751 6d. “for mending ye Chancel Window.” At the back of his book he copied out lengthy extracts, in Latin, from a very dull treatise on Logic.

This then was Charles Scott, as far as we are able to judge. A highly educated man of cultured tastes, happiest in his garden and in his little agricultural operations, respected very likely by his equals and probably treating his parishioners (so long as they made no demand on his purse) with a certain kindly dignity. Differing in no way (save that he preached sometimes in Church and occasionally celebrated the Holy Communion) from the laymen of his own class who formed his social circle. Delegating all he could to a not-too-well-paid curate. It is futile to attempt to measure a man of this type by any idealised conception of what a Christian priest should be. But he undoubtedly conformed to the unexacting standard of his time and, with a little more backing, he might well have become a bishop.

Four years before his death in 1762 Mr. Scott’s handwriting undergoes a very marked change. The neat copper-plate rapidly deteriorates and becomes a mere complex of thick meaningless strokes. To those familiar with his book the inference is irresistible. The poor old gentleman had become blind.

Part 8 August 1934

On Mr. Scott’s death there came to Compton another shadowy individual. John Michell was instituted rector in April, 1763, he allowed Dr. Shipman to carry on the work of the parish, he spent £111 on re-tiling and repairing the rectory and he left in January, 1765, on being appointed rector of Havant.

And now an act of tardy justice was done, for Dr. Robert Shipman was himself made rector. He had come here 25 years before (at the age of 26), a clever young man from Oxford, full of academic honours, and there seems to be no doubt that it was he, and not the rectors he served, who had provided for the spiritual needs of Compton folk. He was a worker, he was generous, and it may be said truly that all we know of him is to his credit. One visible trace of him, by the way, we still have with us. The Parsonage Barn (on the west side of the present post-office) was rebuilt by him in 1771 at a cost of about £150 and it remains today probably very much as he left it.

Dr. Shipman died in October, 1775, and there followed an almost comic interlude of five months which represents the rectorate of Dr. Newton Ogle, Dean of Winchester and father-in-law of Sheridan the dramatist. He was a busy man and it could hardly be expected that he would devote himself much to Compton, but he did find time to call a-meeting of the tithe tenants, as a result of which the latter found their contributions increased by about 25%. One feels therefore that the good Dean would retain at least one pleasant memory of his connection with our parish. In March, 1776, he secured for himself a very rich benefice in Southampton, one of the financial “plums” of the diocese, and Compton knew him no more.

It was at this time that George Isaac Huntingford was working here as a curate, and the fact that he is the only Bishop buried in our church demands for him more than a passing reference.

In 1774 Huntingford, then a tutor at Winchester College, became involved in a “revolt” at College when 40 boys, having unsuccessfully demanded his dismissal, left the College for their homes. He himself evidently thought that a change of work was desirable and, as Dr. Shipman’s health was failing, he became curate here early in 1775 and remained about 18 months. This was evidently a very happy period of his life for he always had a great affection for the parish and, in later years, came to officiate from time to time at the Church.

In 1785 he was back at Winchester College again, was appointed Warden shortly afterwards and retained the position for 42 years. He became Bishop of Gloucester in 1802, being translated to Hereford in 1815. His relations with his dioceses throw a curious light on the period. At Gloucester he left no mark whatever and his visits there can only have been very rare. At Hereford it is thought that he occasionally stayed there for short periods in the summer.

It was indeed at Winchester College that his great interests lay, and there his record is not a happy one. His Wardency was marked by periods of great turbulence and indiscipline among the boys. In 1793 occurred the great “rebellion” when the boys imprisoned Dr. Huntingford in his room, seized arms, hoisted the Red Cap of Liberty and victualled and prepared the College for a siege. After scenes which would be incredible if they were not well authenticated order was restored and 35 boys expelled. In 1818 again, in somewhat similar circumstances, the Riot Act had to be read and troops brought in to quell the disturbances. In both these affairs Dr. Huntingford displayed a singular lack of judgement and he cannot escape a share of the responsibility for what occurred. The Wykhamist historians criticise him severely; the kindliest judgment on him being to the effect that he was a good man but did not understand boys. In which case it seems a little unfortunate that most of his life should have been spent as a schoolmaster.

The whole story of Dr. Huntingford is, in fact, that of a well-meaning man of mediocre capacity raised, by the influence of powerful friends, to positions for which he was quite unsuited. It is this which, in the view of the present writer, makes his memorial in our church one of the most pathetic of our monuments. It seems as if the old man, looking back rather wistfully over his life and very conscious of failure, desired that his bones should rest, not in the great cathedral he had neglected, but in the little country church where, had he remained, he might have lived a happy useful life.

Part 9 September 1934

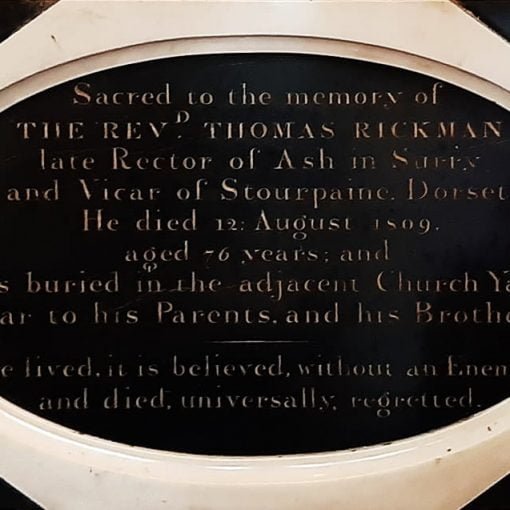

On the departure of Dr. Newton Ogle in 1776 there arrived in Compton a very enigmatic individual, Thomas Rickman. Of most of the post-reformation clergy we know, at all events, where they were educated and what benefices they had held previously. But not so in the case of Mr. Rickman who appears completely out of the blue. The first thing he did here was to enter in the book he inherited from Dr. Shipman details of the fees, gratuities, etc., he had had to pay at his institution to the living. These amounted to over £41 and included two guineas in tips to the Bishop’s servants. Then, in consultation with the parish clerk, George Cole, he wrote out a list of the fees he himself was entitled to charge for his own services. He worked the parish himself, employing no curate, and the parish books and registers in his time are a model of neatness and precision. After five years he resigned, and disappeared from history, “leaving no trace.” One would like to know more of this painstaking methodical person.

The stage was now set for the entrance of the last, and one of the most remarkable, of our pluralists. Philip Williams came here in 1781 at the age of 39 he had been 16 years in Holy Orders and so far no highly-paid sinecure had come his way. Clearly, if he was to share in the good things, he would have to bestir himself, and Mr. Williams, who did nothing by halves, set to work with a will.

In those days one of the less obvious paths to lucrative preferment lay through the chaplaincy to the Speaker of the House of Commons, an office of which the chief duty was to read the prayers with which that assembly opens its daily sittings. Mr. Williams was private chaplain to the Earl of Liverpool and it may well have been through the latter’s influence that in 1783 our rector obtained the coveted appointment. Be that as it may, we find that in August 1784 there was moved in the Commons “an humble address praying the Crown to bestow preferment on their Chaplain.” It says little for the gratitude of George III that Mr. Williams was kept waiting for five years before he received a prebend’s stall at Canterbury. Meanwhile, however, he had obtained a similar position at Lincoln, where, it may be noted, he held the office for 48 years, apparently without doing any duty there at all.

In 1797 Mr. Williams, reflecting perhaps that, as an astute prelate had remarked long before, “Canterbury hath the higher rack but Winchester the deeper manger”, exchanged his stall at the former for one in our own Cathedral. In the same year a timely vacancy in the rectorate of Houghton enabled him to add the income of that benefice to his revenues.

Having thus placed himself beyond the reach of want Mr. Williams settled down to a busy life in Compton. For this rector was no idler and, whatever else he may have neglected, our records show clearly that he did his duty in our parish, and did it well. The archives of Winchester Cathedral Chapter also bear abundant witness to his manifold activities in that quarter, and there is no doubt that a very notable figure passed away at Christmastide in 1830 when, at the great age of 88, Philip Williams died.

And here these notes must end, for the period we have reached, being within the lifetime of the grandparents of some of us, cannot be described as the days of long ago. And furthermore, a new and a better chapter in the history of the Church of England was opening. Whatever view the individual may take of the respective merits of the Evangelical Revival and the Oxford Movement it is not to be denied that, between the two, in the space of a single generation, the religious life of the average English parish was revolutionised — and incidentally the life and outlook of the parish priest.

And yet one may be forgiven for finding a certain picturesque attractiveness in the clergy of the olden days, even where their shortcomings are concerned. When, in years to come, another chronicler sits down to write the history of this last century in Compton, he will find a great deal to tell of lives of self-sacrifice spent here, of increased devotion, of efficient organization and of much-loved priests. But he will miss the “purple patches” which enliven the story of the good old days.

Notes from the Rector, Philip Cunningham October 1934

The first thing in this Magazine is to record our very best thanks to Mr. J. S. Drew for the articles he has been writing in the Magazine on Compton Clergy of long ago. It only requires a little imagination to perceive that these accounts of past Rectors are the result of long and patient work amidst the Registers and documents of the Parish and Diocese, and of enquiries made at places far outside the Diocese, as for instance, at Lincoln. It is to be hoped that these articles, which represent work that has never been done — or done at least so adequately — for the Parish before, have been duly appreciated by those who have read them, and that there are some who will preserve them. The experience of those who are responsible for the magazine is that while complaints and criticisms are quite common about its short-comings, there are very few who are inclined to lend a hand and make it more lively and representative than it is. And in the case of this series of articles of Mr. Drew’s, how many have thought it worth while to express their appreciation of them!

Rev. Philip Williams – October 1935

A year ago there appeared in these columns some notes on the Rev. Philip Williams who was rector of this parish from 1781 to 1830. These notes chanced to meet the eye of Mrs. Jervoise, a great-great-grandchild of Mr. Williams, and with great kindness she allowed the writer to examine (among other papers) a series of letters which passed between Mr. Williams and his wife during the years 1784 to 1787. Though they are concerned, naturally enough, mostly with family and social matters they throw a certain amount of light on church life in Compton.

At this time our rector spent the greater part of each year in London where he was chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons. This, by the way, was Mr. Speaker Cornwall whose engaging habit it was, during the debates, to keep under his chair a tankard of porter, from which he was wont to refresh himself as occasion arose. Mrs. Williams lived with her four small children in Kingsgate Street, Winchester, until 1786 in which year the family moved to Compton Rectory. It was the laudable custom of this husband and wife, when parted, to write to each other every week.

It must, in the first place, be confessed that in the former notes an injustice was done to Mr. Williams’ powers as a collector of lucrative appointments in that he was credited only with the simultaneous holding of prebends’ stalls at Canterbury and Lincoln, and the rectories of Compton and Houghton. It now appears that in addition he was Bursar of Winchester College and Vicar of Gosberton in Lincolnshire. At all events these responsibilities sat lightly on his shoulders and his references to them are rare. He moved in a high social circle and his naive accounts of how he cultivated the acquaintance of those who had patronage to bestow make very amusing reading. His wife however did not approve of these demarches. “I had rather” she writes “see my poor Phil a country curate his whole life with some feeling and humanity, than at the top of his profession in Westminster Hall, if it is to be purchased by the sacrifice of every amiable virtue and sentiment.” In this she does him little less than justice for he was never spoilt by success, as is shown by his great popularity among all classes in Compton.

Mr. Williams seems usually to have employed a curate, and his wife was zealous in seeing that, in his absence, Morning and Evening (said in the early afternoon) Prayer was read each Sunday. Indeed during a gap between two curacies it was she who arranged with neighbouring clergy (and Winchester seems to have been full of them) to conduct the services in our church, and she spent each Sunday in Compton herself to see that all went well. One of the Heathcote family often officiated in this way to her satisfaction but not every visiting clergyman created such a good impression. Thus a rector from Winchester seemed to Mrs. Williams “so bloated and puffed up” that she doubted whether he would be able get through his sermon, while little Philip Williams (aged 4) caused much embarrassment by calling public attention to the shabbiness of another minister’s coat.

To this capable girl (who seems to walk straight out of the pages of Jane Austen) the Church services were a matter of constant concern. When a new servant applies for a situation the fact that “he is a great man for church musick and will assist the Compton choir” weighs heavily in his favour. And when her husband for once shows slackness she goes to the very limit of what was permissable in an 18th century wife. Thursday, July 29th, 1784, had been appointed a day of National Thanksgiving for the termination of the war against the United States, France, Spain and Holland, and special services were ordered to be held in every church. Listen to what happened here in Compton.

Philip Williams to Sally. 17th July, 1784.

“I shall not wish Heathcote to take any notice of ye thanksgiving ; in so small a place n’importe, and pray tell him so.”

Sally to Philip. 18th July, 1784.

“I have written to Mr. Heathcote about the thanksgiving, and if he cannot do the duty I shall get it done if I make a sermon myself ; as I think the obligation indispensable upon you to take care that there shall be no relaxation in attendance upon your flock in your absence, and particularly upon such a remarkable occasion as this in question ; it is no excuse to the Comptonites that you have bought some oxen and must go to prove them. It is very audacious in me to say this, but I trust you will not be angry, and so in spite of you there shall be a service on the 29th.”

The sermon however never materialised.

Sally to Philip. 1st August, 1784.

“There were prayers only at Compton on the thanksgiving, and a very good congregation, which I am glad of, as it is a proof that they deserve to be attended to.”

Poor Sally Williams! She was barely 30 when she and her baby died, but she has her place among those to whom the Church in Compton owes something.

Further Reading

Fig 1. John Summers Drew (1879-1949). Compton near Winchester – being an Enquiry into the History of a Hampshire Parish by J.S.Drew. Published 1939 by Warren and Sons, Winchester, cover price 12/6

- John Summers Drew (1879-1949): a Neglected Hampshire Historian, by Barbara Turnbull in Volume 48 of the Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club & Archaeological Society.

- Footsteps from the Past: Events in the times of Parish Priests of Compton All Saints. https://lhs.comptonshawford.uk/portfolio/footsteps-from-the-past/

- James Wedderburn, Rector of Compton 1626-1636, by John Widdows, Rector 1999-2003, for the Compton & Shawford Parish Magazine November 2000 and March 2001. Available online at https://lhs.comptonshawford.uk/portfolio/james-wedderburn/

- Compton & Shawford – The Story of a Quiet Parish, by Barbara Clegg. Dated 1963, unpublished until a limited edition was printed in 2019 in aid of church funds.