7 Dec 1923-13 October 2024

A Tribute – Wednesday 6 November 2024 Chesil House, Winchester

By his nephew Sandy Nairne CBE FSA

James Nairne, who died peacefully at home in Winchester on October 13, was widely admired as a man of courtesy, diligence, loyalty, dignity and modesty; qualities he combined with a refreshing sense of humour, both about himself and the world. He was a details man, and it won’t surprise you to know that many years ago James wrote his own draft of what might be said today: not to edit his life but simply to save someone else – i.e. me – from having to research all of his achievements (or get it wrong) … Thank you, dear Uncle James.

1

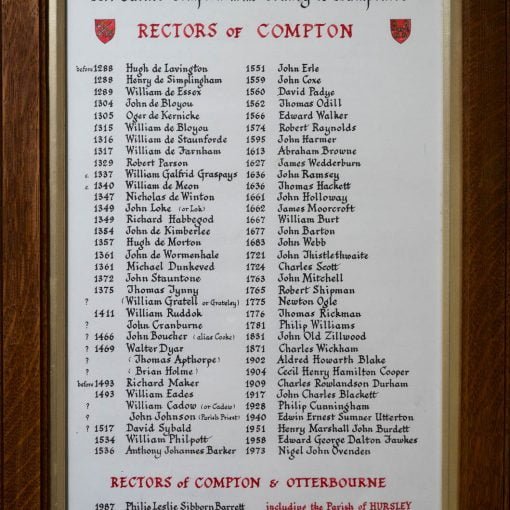

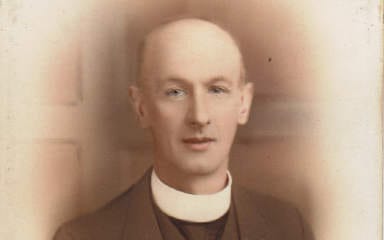

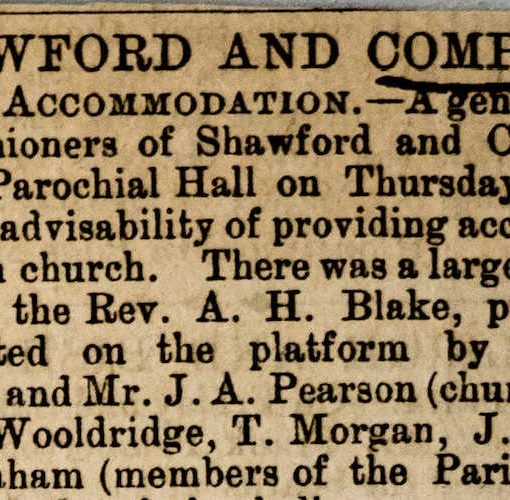

As you all know, James lived for a very long time; to be precise 100 years, 10 months and 6 days. For most of that century and despite his travels and adventures and allegiance to Scotland, Winchester was his key reference point. The third of four boys, James had a happy childhood at Plover Hill, a house built by his parents – Lieutenant Colonel Charles Sylvester Nairne and Edith Dalmahoy Kemp – above the village of Compton with a fine view across the valley to the Cathedral.

Plover Hill offered well-ordered family life: chilly but quite cultured, with golf or painting expeditions on the Downs, church on Sunday and friends and fruit cake for tea. Alongside some fiercer elements as a regular army officer, Charles Sylvester was a talented artist and Edith was an active member of the Shawford Players. The Nairnes were good Scots, and my father described how their parents also conformed to the accepted conventions of their class: ‘Good behaviour … was of prime importance.’

James spent his teenage years at Dauntsey’s School, but in 1937 his eldest brother Sandy died following a ruptured appendix, aged just 17. This was devastating. However, James spoke later in life of how the loss was never discussed within the family. With Sandy gone, Patrick was now eldest, James second (but tallest) and David became the third. The brothers remained close. Though, after a successful career in the Royal Navy, David very sadly died in his late 60s, in 1998.

2

As soon as he left Dauntsey’s in 1942 James enlisted in the Seaforth Highlanders, his father’s regiment, in which Patrick was already serving: the start of 17 years of army service. The Seaforths have a proud history, being one of only two regiments with a gaelic motto – koo-jich ‘n ree – (Cuidich’n Righ)- Serve the King.

After initial training, James landed on Gold Beach in Normandy on D-Day +1 : – 7th June 1944. As a rifleman in B Company of the 2nd Battalion Seaforth Highlanders, he fought in the North West Europe Campaign, and then as Corporal Nairne he crossed the Rhine in March 1945. By the end of the year he decided to stay in the Army and applied for officer training, soon being granted a regular commission as Lieutenant Nairne.

As a regular commissioned officer after the War, James served in Gibraltar, Egypt, Malaya, South Yemen and Germany. His work involved both active service and army management and in 1959 he was promoted to the rank of Major. But in that same year the Army sent him on a business training course in Glasgow and he decided it was time to retire. It’s characteristic of James that for the rest of his life he was an active supporter of the regimental association of the Seaforth Highlanders and for some years was Honorary Treasurer and Assistant Honorary Secretary.

3

James may have left the Seaforth Highlanders but he didn’t leave Scotland, joining ‘The Scotsman’ newspaper based in Edinburgh, and after a few years became their Assistant Advertisement Manager. We get a flavour of the time from James’s own account of how his ‘main task was preparing the lay-out for the daily edition’ and since he had ‘never been much of a mathematician’ this wasn’t easy; but more difficult was ‘pacifying a sub-editor whose special piece had to be held over in favour of an advertisement on its way by train from London.’ A pre-digital age indeed.

By 1965, now in his early 40s, restlessness led James to look for a more demanding role. As a single person and imbued with a spirit of public service, James was well qualified to become a Queen’s Messenger, a job requiring dedication night and day, total discretion and considerable reserves of patience. The work involved conveying confidential documents for the Foreign & Commonwealth Office to British embassies and high commissions worldwide. Journeys could be complicated, such as visiting Ulaan Baator, capital of Mongolia, 38 hours by train across China, carrying his own spirit stove and supplies, because eating local food was deemed risky.

James may have left Scotland, but Scotland never left him, and he maintained regular contact with army and family friends north of the border. But after nearly 24 years of service he retired at the end of 1988, having completed an astonishing 890 journeys – for which he kept meticulous diaries – missing only one due to sickness. He travelled with 75 different airlines over 5 million miles to deliver (by his own count) 16,306 diplomatic bags (occasionally including surreptitious supplies of Walls pork sausages or Coopers’ Oxford marmalade) and with the bags given their own airline seat next to his. An amazing record.

Iain Bamber, formerly Superintending Queen’s Messenger, wrote recently about James, ‘Queen’s Messengers were by nature quiet and self-effacing, and James Nairne was no exception in these qualities. He was a very Proper Officer and a Gentle Man and I consider it both a pleasure and a privilege to have known him.’

4

Travel allowed James to pursue two of his special talents: watercolour painting and tapestry.

The first was a family tradition, but within that tradition James forged his own strand, by painting exquisite watercolour postcards, recording locations and views and adding messages on the reverse in his excellent italic hand. Many hundreds survive him and are treasured.

Tapestry was portable and a way of filling spare time overseas. He produced a kneeler for Gordonstoun School and another for the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.

Once retired, other interests filled his time: as calligrapher to the Imperial Society of Knights Bachelor; as archivist for the artist Derek Hill, and also for the papers of General Sir Richard O’Connor; and at Winchester Cathedral: serving as a Sidesman for eight years and as a member of the Council of the Friends for more than ten.

5

None of us knows how long we’ll go on, and James can have had no conception of what his later life would bring. But living in his own flat in Winchester, surrounded by his paintings, his sketchbooks and diaries, along with regimental momentoes, was hugely important. When he could no longer travel this was where he wanted to see family and friends. This later life was made possible by wonderful carers (some of whom are with us today and to whom the family are hugely grateful); and it’s a mark of credit to James that he was so popular that the agency had him booked for 18 months ahead.

One of the carers wrote to say that she found ‘he was a man of great depth, able to fill even the simplest of conversations with wisdom and warmth.’ He always cared about the carers, checking on how they were doing.

She addressed James to say, ‘… Caring for you no longer felt like a duty; it became an honour, like caring for a beloved grandfather or uncle.’

6

In James’s own draft for this Tribute, he accurately referred to himself as a ‘tall, fine-looking man.’ And went on to write (in the third person): ‘His shyness and reserved manner … remained with him … At first meeting he would often be silent, creating a misleading impression of his character. But, while he would appear outwardly as a rather private person, there was also an opposite side marked by a long memory, a fund of humorous stories, and a gift for mimicry.’

His mimicry and stories were certainly very funny, but more than anything James cared about fellow soldiers, colleagues, friends and family. He was an exemplary uncle and great-uncle, always thoughtful and generous to his nephews and nieces and their children, as he was to his wide circle of friends.

Age may finally have taken James away from us, but nothing will take away our memories of his great spirit or our delight in his paintings.

James was a fine Scot, a fine soldier, and although it may sound slightly old-fashioned: a very fine gentleman.

Editor’s notes: Tribute as printed in the January 2025 Compton & Shawford Parish Magazine, by permission of James’s family.

James’s memories of growing up in Compton during the 1920s and 1930s were printed in the January and February 2024 issues of the Magazine and on this website at Growing up in 1920s/30s in Compton and Shawford